Criminal Profiling and Archaeology

Investigating Myth and Ritual - Practices

![[QFK Logo]](qfklogo.GIF)

Use of Myths in Ancient Education

Myths were the mainstay

of ancient Greek education for thousands of years. Homer and the bards

before him were the primary educators, entertainers, historians and theologians

of their time. They sang their stories with musical accompaniment, and

had formulas to help them recall and recount the stories. Some classicists

believe that bards used writing to help them remember their lines, treating

their scrolls as a guild secret, retiring occasionally to a private location

where they could “consult their muse”. Bards either retold old stories

or adapted their stories and formulas to relate recent events. At least

one scholar believes that parts of the Iliad are adaptations of an older

Mycenean siege story (see Beck, F. (1964) "Greek Education 450

- 350 B.C." Barnes and Noble). Also, ancient myths like those in the

Iliad and Odyssey contained history, traditions, values, geography and

more.

Though initially developed in an oral culture, ancient Greek myths

continue to be conveyed using many different media including writing, sculpture,

painting, and television. Many ancient Greek plays were based on or incorporated

myths. Philosophers used myths when educating youth in Athens. More recently,

the mythical journey described by Homer in the Odyssey was adapted for

television, effectively transmitting information from thousands of years

ago into the homes of millions like a modern bard. Greek myths are evidently

so powerful that they continue to live on long after the oral tradition

had faded. Much of the power of myth lies in its content and form. The

content is fundamental information about the world while the form conveys

this information in a concise dramatic way. However, the ancient Greek

myths would not have survived if they had not been adapted to fit new times,

people and places.

Myth Adaptation

As Greek civilisation

became more advanced the myths became more sophisticated. Myths began to

incorporate history, politics, geography and important individuals. An

excellent example of myth adaptation involves Europe, the daughter of a

Phoenician king and the European continent’s namesake.

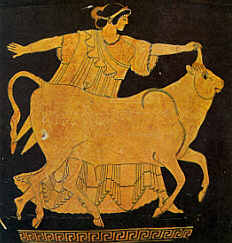

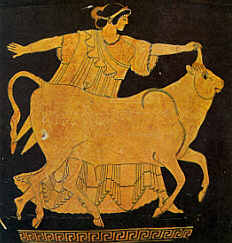

Europe being abducted by Zeus in the form of a bull

Europe being abducted by Zeus in the form of a bull

The Greeks abducted Europe from her native land and brought her to Crete.

However, the associated myth tells us that Zeus was so enamoured with Europe

that he turned into a beautiful bull and carried her across the sea from

Phoenicia to Crete were she bore him three sons, Minos, Sarpedon and Rhadamanthus.

You might ask why did Zeus have to turn into a bull to achieve all of this

and how could this coupling actually result in three human children? Two

pieces of information shed light on this myth. Firstly, the bull was a

very significant animal in the religious systems of both Phoenicia and

Crete.

Bull's Head Rhyton - c1600 BC Palace of Minos (photo

by Dilos Holiday World)

Bull's Head Rhyton - c1600 BC Palace of Minos (photo

by Dilos Holiday World)

Secondly, some of religious systems at the time were orgiastic cults

involving a kind of temple prostitution. The sexual rites performed in

the temple often resulted in children.

“In Greece the children begotten in temples were not frowned upon.

They were, in fact, formally taken to be offspring of the gods of particular

temples. Although Europe has no less than three such “children of the god”,

she was taken to wife by Asterius of Crete and Knossos, who adopted her

sons, Minos, Sarpedon and Rhadamanthus.” Wunderlick,

H. G., (1975), "The Secret of Crete". London: Souvenir Press

So, one plausable theory is that Europe was abducted,

was a temple prostitute for a time and gave birth to her three sons and

the myth were created to add a glamour and legitimacy to Europe’s life

and progeny once she was married to Asterius or after her son Minos became

king. “Minos, son of Zeus” is much more impressive than “Minos, illegitimate,

father unknown”. A related myth, possibly created by the rival Athenians

to insult Minos, claims that his wife Pasiphaë was so taken with a

white bull that she had the resident genius Dedalus build a wooden cow

that she could climb into and have sex with the bull. According to this

myth, the coupling resulted in the birth of the Minotaur.

“Pasiphaë, King Minos’ wife, was of the same kind of parentage:

she was a daughter of the god Helios. Of her seven children at least one,

the Minotaur, was not her husband’s; it was probably begotten “in the temple.”

Nor is it difficult to guess what temple, since the boy was given the name

“Bull of Minos”. In all probability Pasiphaë’s son was sired in the

temple of Ptah (or Baal), the supreme god of the Egyptians of Lower Egypt

and of the Babylonians, who at various times was also worshipped in Phoenicia

and Asia Minor.” Wunderlick, H. G., (1975), “The Secret

of Crete”. London: Souvenir Press Ltd.

This stream of myth adaptation continues with the myth of Minotaur in his

labyrinth killing Athenian youths that were demanded by Minos on a regular

basis. If you are interested you can investigate the origins of this murderous

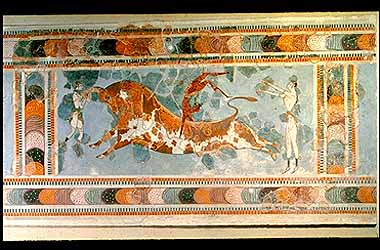

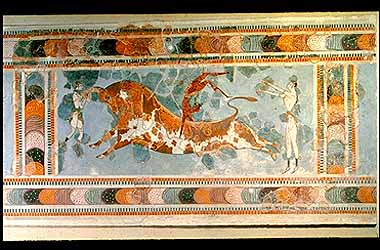

myth. To get you started, consider this fresco found at the Cretan site

at Knossos depicting youths leaping over (or being gored by) a bull.

The Toreador Fresco - c1500 BC Palace of Minos (photo

by Dilos Holiday World)

The Toreador Fresco - c1500 BC Palace of Minos (photo

by Dilos Holiday World)

Also consider that the first person to excavate the site, Arthur Evans,

had the preconception that the site was the palace of Minos and believed

that he had found a labyrinth on the site. If you would like to share your

thoughts about this myth or learn more you can e-mail

me.

So, early rituals and myths about bulls and temple

prostitution were adapted over time to form new myths that included modern

events, politics, people, etc. It is also interesting to note that certain

practices evolved from myths.

For example, the ancient Olympics grew out of a myth about Pelops’

chariot race across the Peloponnese (named by Pelops after he became

king) against the then king Oenomaus. If you visit Olympia, the site of

the ancient games and the namesake of the modern Olympics, you will find

the tomb of Pelops.

For example, the ancient Olympics grew out of a myth about Pelops’

chariot race across the Peloponnese (named by Pelops after he became

king) against the then king Oenomaus. If you visit Olympia, the site of

the ancient games and the namesake of the modern Olympics, you will find

the tomb of Pelops.

Criminals also develop and change their personal

myths over time, incorporating new ideas and experiences. Something unusual

can happen during a crime or something can happen to the criminal in his

everyday life that influences him and causes him to modify his behaviour.

Such a modification will cause an associated adaptation in the personal

myth that he uses to explain his behaviour. In this way, myth acts as an

adaptive interface between ritual and the outside world. For more on adaptive

interfaces see.

Ted Bundy’s modus operandi

changed significantly over time from very careful to extremely careless.

Though this change in behaviour was probably caused by his increased alcohol

intake, he undoubtedly adapted his personal myth to accommodate the change.

It is crucial for investigators to realise that criminals’ personal myths

will probably change over time. An investigator should not expect the criminal

to do the same thing every time, making it easy for the investigator. A

part of understanding a criminal and his personal myth is to understand

how his behaviour changes over time and how he adapts his personal myth.

To reiterate, these personal myths have their own logic and values that,

once understood, can be used to understand the criminal and even predict

future actions.

Reconstructing Myths

Heinrich

Schliemann, now famous for finding ancient sites that most of his contemporaries

considered to be mythical, had a passion for Greek mythology since his

childhood. He worked himself from poverty to riches and in his forties

followed his childhood dream of finding the ancient sites that he had read

about in Greek mythology. Though his approach of referring to ancient texts

as factual was successful, many experts ridiculed him for his unorthodox

approach, arguing that myths were just stories with no historic foundation.

Schliemann did deserved criticism for many aspects of his archaeological

approach since his inexperience resulted in the destruction of much of

what remained at the ancient sites. However, he did not deserve criticism

for his belief that the ancient myths, stories and texts contained useful,

often factual information. Schliemann was the first individual realised

the importance of incorporating ancient Greek mythology into his investigations

and for that he deserves praise. Schliemann’s method of using myth brought

about a significant change in archaeology – purposeful excavation.

Schliemann looked through ancient mythology to find ancient

sites and learn about ancients

Schliemann looked through ancient mythology to find ancient

sites and learn about ancients

Shortly after Schliemann’s death, Arthur Evans followed

in his footsteps by buying and excavating the site of Knossos in Crete.

Schliemann had been convinced that the site was the palace of the kings

of Knossos but had not been able to purchase it. Though Evans was more

methodical and scientific than Schliemann in many ways, he was more careless

in his use of myth and ancient texts. Even worse, Evans used his own preconceptions

to recreate much of the site. In essence, Evans excavated and recreated

what he believed was the palace of Minos with its vast labyrinth that contained

the Minotaur. Every conclusion and reconstruction was based on the assumption

that this was the palace of Minos. Evans made his job easier by claiming

that the incredible, peaceful civilisation that he called the Minoans had

grown out of nowhere and disappeared mysteriously. In this way, he did

not have to look for similarities between what he found and what was found

in nearby excavations in Greece, Asia Minor and North Africa. Needless

to say, Evans’ use of mythology in his reconstruction was ultimately criticised.

However, there are many scholars today that still believe that Knossos

was Minos’ palace and that the Minoans were a perfect race that blossomed

and died independent of surrounding civilisations. In fact, the site at

Knossos is still presented to visitors in this way.

Evans looked at Knossos through the wrong myths and missed the

point entirely

Evans looked at Knossos through the wrong myths and missed the

point entirely

The process of using myths to find and excavate ancient sites is the

reverse of the process of using evidence at a crime scene to recreate a

criminal’s personal myth. However, the processes are parallel and we can

learn valuable lessons by comparing them. The lesson here is that there

is a balance to be made between too little and too much myth. Investigators

that do not use myths can miss a great deal, while investigators that use

too much myth can misinterpret what they find. There are two relevant and

common examples in the domain of criminal investigation. Like Arthur Evans,

many investigators walk into a crime scene with a preconceived notion of

what happened. These investigators are only interested in proving their

theory and therefore overlook contradictory evidence. These investigators

are not interested in spending the time necessary to understand the criminal’s

personal myth. For an example of too much myth, consider the use of psychics

in a criminal investigation. Psychics are sometimes called in when investigators

have run out of leads and are disheartened. Psychics proclaim that they

are able to pick up on things that other people can’t, including what is

going on in a criminal’s mind. Though these claims have never been proven,

investigators often rely on psychics and are often misled by them. Such

an overuse of myth in an investigation can put peoples’ lives at risk and

is therefore dangerous and inexcusable.

Wunderlick, in his book “The Secret of Crete” presents a vivid example

of how Evans’ investigation into ancient culture went awry in a way that

is remarkably similar to many criminal investigations. Wunderlick encourages

investigators to combine science and mythology to reach an understanding

of ancient cultures.

“Ever since the inception of the science of archaeology there have

been those who place their trust in the oral tradition as set forth in

myths and legends, and those who trust only what the spade turns up. …

There is something fundamentally misleading about the dispute over whether

to believe oral tradition or the result of excavation, as though one approach

excluded the other. The archaeologist who carries out his field work with

scientific vigour, but views his findings only through the lens of his

own experience and the attitudes of his own day, will obviously go far

wrong. He will derive at least as false a picture as the mythologist

who sets out to interpret ancient traditions with sovereign unconcern for

time, space and the yield of excavations. By itself, neither tradition

nor excavation is sufficient. Both must be combined to form a logical whole.

But when we speak of logic, we do not mean to imply that, for example,

it is necessary that the ancient rites for the dead or conception of the

hereafter be logical in the modern sense. Any acquaintance with mythology

should make us aware that the thought processes of the ancients were totally

unlike our own. Once we have realised that, we should be very chary of

imposing our cultural preconceptions on ancient peoples.” Wunderlick,

H. G., (1975), “The Secret of Crete”. London: Souvenir Press Ltd.

There is a similar struggle to get criminal investigators to synthesise

the results of scientific, sociological and psychological analyses without

letting their egos get involved. Many forensic scientists believe that

physical evidence is the most important part of an investigation while

many sociologists, psychologists and criminal profilers believe that they

can determine a criminal’s personal myth with very little physical evidence

like Evans the archaeologist. To make matters worse, there are many instances

in which investigators defend their erroneous conclusions in a case even

when presented with contradictory evidence. When investigators resist valid

contradictions it is usually because their egos are involved or there is

a political component to the case. Perhaps people who cannot see the damage

that they are doing in a criminal investigation will find it easier to

learn from the less personally threatening mistakes that have been made

by archaeologists in similar situations. Perhaps then achieve a synthesis

of hard and soft science that enables them to become better investigators

and possibly even criminal profilers.

The best criminal profilers comb through all of the physical evidence

that they can lay their hands on and carefully reconstruct the crime, the

criminal’s behaviour and the criminal’s motivations and fantasies. This

ideally objective synthesis leads to a more complete understanding of the

criminal and can help enormously in an investigation. For example, in a

recent serial killing, the suspect was denying that he had committed certain

acts. However, after combing through all of the available physical evidence

and looking through many of the suspects personal effects such as books

and music, the criminal profiler working on the case determined that the

suspect had a secret hiding place where investigators would find additional

evidence. Sure enough, when the investigators brought the criminal profiler

to a location in the hills that the suspect frequented they dug up important

evidence that cause the suspect to change his story. The criminal profiler

had essentially reconstructed the suspect’s behaviour and view of the world

to know what to look for. Though time consuming, this reconstruction process

is invaluable in an investigation.

Read the Artifacts section of this work for the

practical ramifications of this work.

QFK | Investigating

Myth and Ritual - Main Page | Ideas

| Artifacts

QFK | Investigating

Myth and Ritual - Main Page | Ideas

| Artifacts